How foreign direct investment is changing—and why it matters

Shifts in greenfield FDI are shaking up the industries of the future and rewiring global trade

By Olivia White and Tiago Devesa

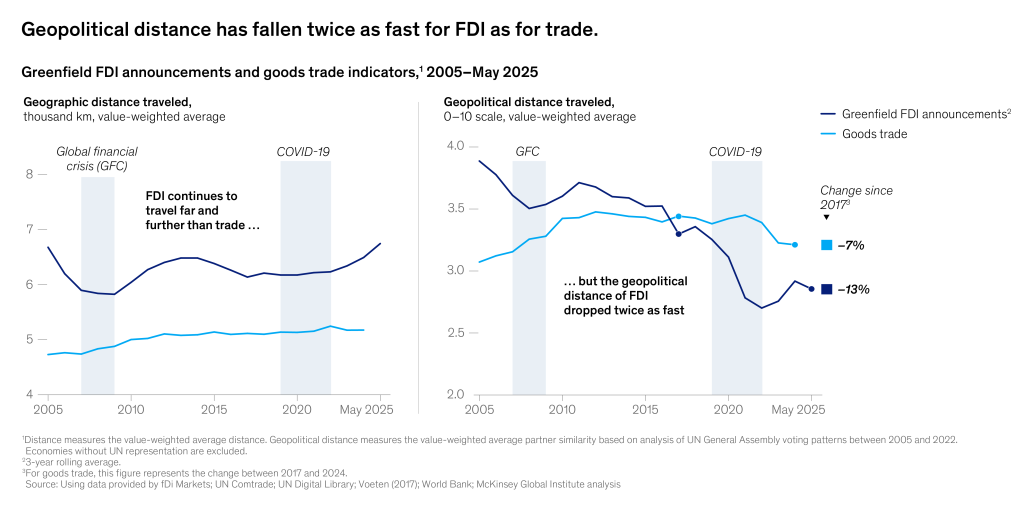

Geographic distance is easy to understand: look at a map and countries that are eight centimeters apart are obviously more distant than those three centimeters apart. “Geopolitical distance” is a more sophisticated idea: it refers to how closely aligned trade and investment partners are. Japan and the United States, for example, are close geopolitically. Germany and Russia are not.

Until roughly a decade ago, geopolitical distance was a minor factor in trade connections and cross-border investment decisions. When companies forged globe-spanning supply chains, efficiency and financial returns were top of mind; politics was, perhaps, a distant third. As a result, geopolitically remote countries found themselves depending on each other for critical goods, ranging from natural resources to advanced manufacturing. Of course, it is routine to do business with companies and countries that one wouldn’t want to invite to a dinner party. Nevertheless, the result is that many of the connections created in the 1990s and well into the 21st century have become sources of discomfort in today’s more fractured world.

New trends in foreign direct investment (FDI), however, might change that. After the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Europe cut off energy imports from Russia, replacing them with domestic sources and natural gas from closer geopolitical partners such as the United States. That hurt at first, but Europe has managed to adjust, because many countries are willing and able to export energy. After all, Russia accounts for under 20 percent of global gas production. And the more Europe diversified, the more its demand has supported the cross-border investment case for more liquified natural gas capacity – including large projects in the United States and Qatar.

In cases where only a few markets provide the input or product, though, matters are more complicated. Countries outside that circle have to attract investment to help secure access. Take semiconductors. Taiwan and South Korea produce 90 percent of the world’s most advanced semiconductors, used in smartphones, artificial intelligence (AI), and defense technologies. When the pandemic disrupted supply chains, companies and countries alike were reminded of just how dependent they were on a handful of companies—for consumer, business, and security applications.

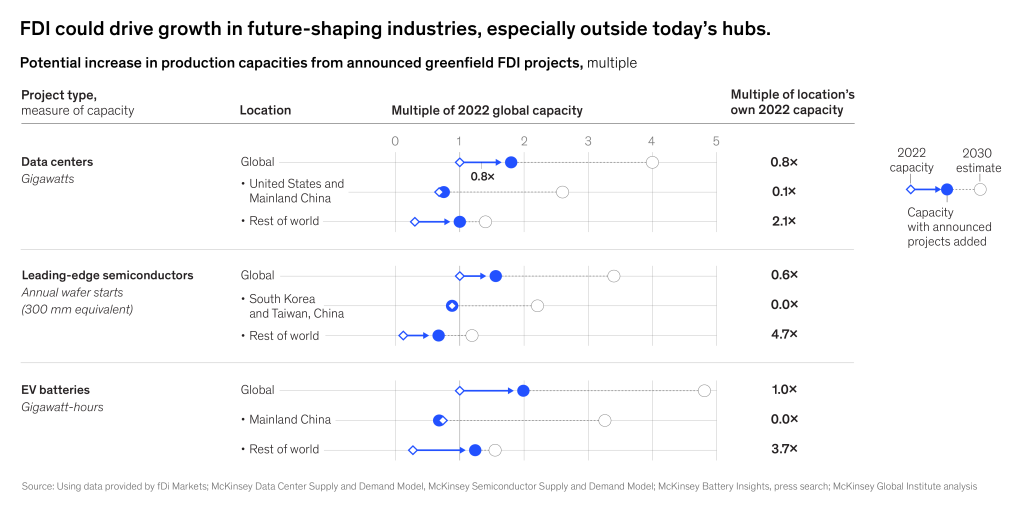

Massive FDI projects, sponsored by firms from Taiwan and South Korea, could make the United States a semiconductor powerhouse by 2030, accounting for more than 20 percent of leading-edge semiconductors and reshaping supply chains in the process. These countries are geopolitically close—and that is probably not a coincidence. Taiwan and South Korea build a bank of goodwill in a country that is critical to their security. The United States gets jobs, expertise, and greater self-sufficiency when it comes to manufacturing the most advanced chips.

But “friend-shoring” isn’t just about shifting current supply and business patterns. An additional element is the desire to build strong connections with like-minded partners in the industries of the future. According to a McKinsey Global Institute analysis of 200,000 FDI projects, since 2022 about 75 percent of greenfield announcements have gone to “future shaping” industries, compared to 55 percent before 2020. These are advanced, knowledge-intensive sectors, including advanced manufacturing, data centers, defense, pharmaceuticals, robots, and the energy and mineral resources needed to produce them. Announcements in these areas are on pace to reach $840 billion this year.

Now is the time to hard-wire these connections—and that is what is happening. Since 2017, the average geopolitical distance of greenfield FDI announcements shrank about twice as fast as that of trade. From 2010-25, advanced economies’ total FDI announcements by value in China fell from 10 percent to 2 percent, while flows among advanced economies, which tend to be geopolitically close, increased from 35 percent to 45 percent.

If the announced FDI investment takes place—and precedent says most of it will—the footprint of important global industries and trade could change drastically.

In the case of electric vehicles (EVs) and the batteries that power them, Chinese companies dominate production. But cars are heavy and challenging to transport—favoring regional production—and mounting trade barriers have made securing market access more important. In the past few years, Chinese firms have increased investment outside China significantly, with new facilities in Brazil, Hungary, India, Malaysia, and Saudi Arabia. At the same time, the United States has attracted significant battery investment from other advanced—and geopolitically close—economies, particularly South Korea and Japan. All told, these FDI-driven gigafactories could quadruple non-China battery production by 2030. And it’s not just about physical goods like batteries and cars. Data centers are another future-shaping industry. Announced projects could come close to doubling their current capacity outside the United States and mainland China.

Changing well-established trade and industry patterns is akin to turning around a massive oil tanker in a storm—doable but difficult. Capital can shift faster and more readily. While the geometry of trade is far from settled, we believe that announcements of greenfield FDI serve as an important signal, long before large-scale shifts in commerce occur.

All this points to a world still connected through trade, but where more is defined by politically informed capital investments, as FDI shifts the global footprint of future-shaping industries. For business leaders and policymakers alike, understanding FDI offers a way to envision where the action is likely to be—and how they can get a piece of it.

Olivia White is a director of the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) and a senior partner in McKinsey & Company’s Bay Area office. Tiago Devesa is a senior fellow at MGI, based in Lisbon.